Dan Malleck: Habitual risk: Insurance, professional authority and the medicalization of addiction in the 19th century

Posted on 03-09-2013

In his influential textbooks on medical jurisprudence, Alfred Swaine Taylor observed that the opium habit, while generally a personal vice, was viewed by the emerging life insurance/assurance industry as a risky behaviour that might preclude an individual obtaining life insurance coverage. Taylor and others, such as the equally influential Robert Christison, debated in the pages of their books, the truth of this statement: whether opium habit limited life spans, and should be considered by the medical profession as something more than a personal problem, however iatrogenic it may be. When examining the medicalization of addiction, historians have tended to look to two sources for epistemological

roots: medical science and the law. Yet neither of these forms of knowledge is removed from other social, political and economic influences. Like many professionals establishing both their authority and their financial viability, physicians were drawn to the insurance industry as a source of investment to secure their financial future. They were also wooed by the industry, since a medical doctor’s certificate was useful, and eventually required, to guarantee that the

applicant for insurance was healthy enough that insuring them did not pose an undue risk to the company and its investors. By the end of the century, many insurance companies were hiring physicians to manage corporate divisions dedicated to assessing risk, physician groups were setting prices for the medical exam (paid for by the insurance company) and medical literature on a range of illnesses often included commentary on how that illness might affect

the patient’s ability to obtain insurance. This paper looks at how the symbiotic but often fraught relationship between physicians and insurance companies affected the idea of habit as a medical condition. It uses the example of Canadian medical literature, highly influenced by both British and American developments in medical science and medical professionalization, to explore the intricacies of this relationship and whether and how life insurance affected

medical ideas. It posits that historians need to pay attention to the influence of private industry which, even if not directly involved in the practice of medicine (such as the pharmaceutical industry), may have had considerable impact on the development of a disease theory of addiction.

roots: medical science and the law. Yet neither of these forms of knowledge is removed from other social, political and economic influences. Like many professionals establishing both their authority and their financial viability, physicians were drawn to the insurance industry as a source of investment to secure their financial future. They were also wooed by the industry, since a medical doctor’s certificate was useful, and eventually required, to guarantee that the

applicant for insurance was healthy enough that insuring them did not pose an undue risk to the company and its investors. By the end of the century, many insurance companies were hiring physicians to manage corporate divisions dedicated to assessing risk, physician groups were setting prices for the medical exam (paid for by the insurance company) and medical literature on a range of illnesses often included commentary on how that illness might affect

the patient’s ability to obtain insurance. This paper looks at how the symbiotic but often fraught relationship between physicians and insurance companies affected the idea of habit as a medical condition. It uses the example of Canadian medical literature, highly influenced by both British and American developments in medical science and medical professionalization, to explore the intricacies of this relationship and whether and how life insurance affected

medical ideas. It posits that historians need to pay attention to the influence of private industry which, even if not directly involved in the practice of medicine (such as the pharmaceutical industry), may have had considerable impact on the development of a disease theory of addiction.

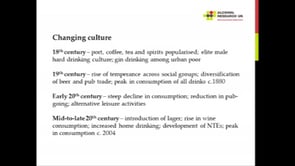

“Under Control? Alcohol and Drug Regulation, Past and Present” conference was held at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine 21-23rd June 2013. Under Control? was supported by the Alcohol Research UK; Bowling Green State University; the Alcohol and Drugs History Society, Brock University (Faculty of Applied Health Sciences); the Society for the Study…